Diamonds in the Rough – Great Managers and Leaders are rare.

According to Beck and Harter (2022), Gallup found in a recent study that one of the most important decisions companies make, is whom they appoint as managers. Their analytics suggest that organisations usually get this decision wrong. In fact, they found that companies fail to choose the candidate with the correct natural talent for the job 82% of the time. In addition, companies fail to develop talent well enough for earmarked individuals to be able to perform in roles to which they are appointed in future.

This is of great concern, as bad managers cost businesses billions each year, and managers account for at least 70% of the variance in employee engagement scores across business units. Thus, when companies get these decisions wrong, there is no quick fix to be found, and they suffer the negative consequences. However, businesses that get it right – by recruiting managers based on natural talent – will thrive and gain a significant competitive advantage.

How do we find those great managers? If great managers seem scarce, it’s because the talent required to be one is rare. Gallup’s research reveals that only one in 10 people possess the inherent, natural talent to manage others effectively. Although many people are endowed with some of the necessary traits, only these few have the unique combination of characteristics needed to help a team achieve excellence in a way that significantly improves a company’s performance. These 10%, when put into managerial roles, naturally engage team members and customers, retain top performers, provide employees with meaningful work, and sustain a culture of high productivity. Selecting managers who fall outside of this 10% results in much time, effort, and resources being spent coaching and training individuals who are in fact square pegs forced into round holes. Regardless of coaching and training interventions, these individuals may simply not thrive in the role of a manager.

Whilst it is true that every manager can learn to engage a team, research has found that it is not an easy skill to master without the raw natural talent to do so. Successful managers are able to individualise, focus on each person’s needs and strengths, boldly review team members’ performance, rally people around a cause, and execute efficient processes. If individuals are not in flow with their work as managers, the day-to-day experience of managing others may lead to burnout for both manager and team.

Conventional selection processes are a big contributor to inefficiency in management practices; they apply little science or research into finding the right person for the managerial role. When Gallup asked U.S. managers why they believed they were hired for their current role, most cited their success in a previous, non-managerial, role or their tenure in their company or field. However, these reasons are unrelated to whether or not the candidate has the right talent to thrive in the role. Being successful in a role such as that of a programmer, salesperson, or engineer will not guarantee that the incumbent will be adept at managing others. Research conducted at Bioss SA further reinforces this notion and indicates that people’s ability to cope with different levels or themes of complexity grows at different rates. It also proves that success at one level of complexity does not necessarily guarantee success in another, more complex, level of work.

Research shows, over and over again, that the practice of promoting workers into managerial positions because they seemingly deserve it, rather than because they possess the talent or potential for it, doesn’t work. While experience and skills are important, it is people’s inherent talents (the naturally occurring patterns in the ways they think, feel, and behave) and their inherent capability to deal with increased complexity – that predicts at which level they’ll best perform.

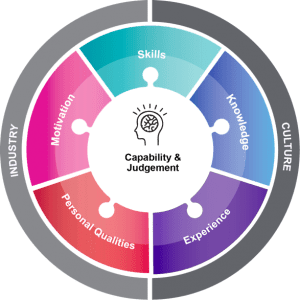

The Model of Potential – shown below – depicts the conventional components of perceived ‘Potential’ as Skills (What can you do?), Knowledge (What do you know?), Experience (What have you done?) and Personal Qualities (What are you like?).

Capability – the central (and often overlooked) piece of the model – is that part of ourselves that we have to call on when Skills, Knowledge, and Experience fail to give us the whole answer. It is what we use to pattern and order complexity and uncertainty, to enable us to navigate it and continue to make sound decisions, even when we do not, and cannot, know the answer.

We know that Capability grows over time. Put simply, someone’s ability to cope with uncertainty is likely to be greater when they are older than when they were younger. What is more, Capability will continue to grow, even when other components in model are fairly static. This is not to say that the other components of the model do not also grow over time. On the contrary, aspects such as Skills and Experience do grow and contribute greatly to the success of managers and leaders.

Capability

There has been work undertaken over many years focused on the central component of the model: Capability. The Capability element is requisite but not sufficient – i.e. we need the other components of the model too, to convert our inherent potential into credible and productive action. This said, the evidence points to the fact that the stronger the Capability element, the more people experience a sense of ‘flow’ at work, irrespective of their inventories in other aspects. An experience of ‘flow’ implies more engaged, productive, and satisfied employees.

The figure below shows how Capability grows over the years, often including the years after conventional retirement.

Chart © Bioss, Growth Curves © E. Jaques

The chart above reflects the following

- Chart with person A and Person B

- Person A is a mode (future potential) Mid Practice (Theme 3)

- Person B is a mode (future potential) Mid Strategic Intent (Theme 5)

- Transition points shown on chart.

The labels along the vertical axis of the growth curves shown above, with their accompanying capability requirements such as Connecting and Modelling, refer to Themes of Complexity. These themes range from the Quality theme, where decisions have an immediate impact and are low in complexity, to Strategic Intent – typically the CEO level of work – where the full impact of some decisions may take up to 10 years to become clear, and where decisions must be made in conditions of uncertainty. Typically, good Supervisors thrive in the work theme of Service; Managers thrive in the theme of Practice; and General Managers and Executives thrive in the theme of Strategic Development.

We all have Capability. What differentiates us is the different paths along which our individual capability grows over time. The sweeping curves in the diagram above illustrate two such different paths. Although our Capability grows in our own individual way, it grows in a consistent pattern across individuals. What this means is that if we can map a person’s current Capability accurately at his or her current age, research reveals that it will continue to grow in a predictable way. Predictive validity studies have shown accuracy at an extraordinary .87, far exceeding most psychometric measures.

Let’s look at the examples in the chart. Person ‘A’ has a classic middle to senior manager profile. At age 30 he is likely to be most effective in a supervisory or specialist role, but with the potential to become comfortable with the work of Management (Practice theme) by his mid 40’s. Going forward, he will be most effective in operational management roles. He will probably not be at his most effective if held accountable for generating and deciding upon strategic options. Rather, he will be in flow adding value for the present. Looking at his predicted growth in capability on the chart beyond age 50, ‘A’ will happily plateau, continuing to make a strong contribution to operational management.

Person ‘A’ at age 50 will have the same capability as Person ‘B’ would have had at age 30. Person ‘B’ thus has a very different journey ahead. Person ’B’ would be comfortable in the Service theme of work in her twenties and transition to the Practice theme of work towards her mid 20’s. Furthermore ‘B’ has the potential to transition into the theme of work called Strategic Development towards her late 30’s, whereafter she will make a final transition into Strategic Intent in her mid-50’s. She is likely to offer her most mature contribution to the organisation in the Strategic Intent theme, typical of CEO work.

Clearly the development plan and the enhancement of the other elements of the Jigsaw will look very different for Person ‘A’ as compared to that of Person ‘B’.

How do we find these great Managers?

More than likely, they are employees with high managerial potential simply waiting to be discovered. They are diamonds in the rough.

What is the difference between managers who are on a steeper path and will transition through more levels in the organisation than those who will move through fewer levels? At Bioss SA our research has revealed interesting results.

What is required?

Comfort with ambiguity and uncertainty – this relates to an individual’s ability to deal with complex problems and limited information (depending on the theme of work of the managerial position). Middle managers need to make decisions about optimising resources and continuously improving systems and practices. CEOs and other executives require a capacity to make decisions and be successful in new, unfamiliar, uncertain, and complex situations. At BIOSS, we use the Career Path Appreciation (CPA) to discover and understand this capability.

Cognitive skills and business insight – Supervisors and specialists (Service theme) are comfortable with accumulating information and tailoring solutions for particular situations, problems or tasks. They tend to solve problems so that they don’t recur. Middle managers (Practice theme) need to be comfortable with systemic thinking, understanding trends in local conditions and valuing control. General Managers / Executives (Strategic Development theme) should be comfortable with parallel processing and business modelling, keeping operations sustainable, but also creating value for the future. CEOs (Strategic Intent theme) must have a capacity to deal with complex and ambiguous phenomena in complex environments. They also display long-term vision and virtue, having a proven commitment to the long-term welfare of not just immediate stakeholders, but of the society within which they operate.

Emotional Intelligence – Successful managers and leaders have strong social skills, self-control, and emotional autonomy. They are able to collaborate and engage resources and stakeholders and tend to be emotionally intelligent and show the ability to read and respond to others’ emotional state so as to ensure constructive interaction.

Openness and reflectiveness – Successful managers and leaders possess self-knowledge; they are introspective and have knowledge of their own limits. They tend to be mindful and are attuned to the world around them. They are open to new ideas and possibilities and are comfortable with changing work environments.

Presence – Successful managers and leaders tend to be articulate and have a proven capacity to reach people through word, affect and action. They display self-control and are able to create the conditions that enable leadership to emerge and ensure support where needed.

Conscientiousness – According to Dr J.B. Peterson, research has indicated that Intelligence is the best predictor of performance whilst conscientiousness is the next biggest predictor. Conscientious managers are industrious, they get things done, and they plan ahead and meet deadlines and targets. Because they are conscientious, they take the time to schedule regular one-on-ones with staff and manage performance and engagement diligently.

Great leaders create clarity

Together, the above components enable a good manager and leader to create clarity for teams. Microsoft CEO, Satya Nadella recently said that one of the traits that every great leader must have is the ability to bring clarity in uncertainty. He notes: “Leaders have this amazing, uncanny capability of bringing clarity into a situation where none exists” and also says that “You can’t call yourself a leader by coming into a situation that is by nature uncertain, ambiguous — and create confusion.” Giving advice on being a leader, he said, “you have to create clarity, where none exists.”

In Closing

Since people with the natural raw talent and capability to manage and lead are so rare, it becomes our job to find ways to recognize these “diamonds in the rough”. We need to find ways of identifying those with the raw natural talent, so that we don’t have to spend a fortune on coaching and training, trying to fit square pegs into round holes.

To summarise, Capability (as measured by the CPA/MCPA) – the comfort with making decisions under conditions of uncertainty and providing clarity to teams in uncertain times – is of prime importance. However, as discussed, it is not the only attribute that a good manager or leader is expected to display. The other elements of the Jigsaw as well as the traits discussed above can also be assessed and developed.

To find out more about “How do we do this”, contact BIOSS SA (info@bioss.com) and we will assist with pleasure!

References

Works of Art, Bottles of Alcohol, and Me (Or how some things do improve with age). (2006) BIOSS Europe.

Ashton, L. (2018). A new generation of leader: The Wise Leader. Bioss SA Blog. (https://www.bioss.co.za/new-generation-leader-wise-leader/).

Beck, R.J., & Harter, J (2022). Why Great Managers Are So Rare. Gallup Business Journal.

Recent Posts

- Are Managerial Development and Leadership Development Programmes the same thing?

- Human Potential: The Differential of the Themes of Work Framework

- Navigating the Future of Work: Balancing Job Automation and Job Autonomy

- Levels of Innovation: Levers of Value-Add

- Three Questions About Managerial Leadership

Categories

- 360 Leadership Survey

- Assessment

- Capability

- Career Path Appreciation (CPA)

- Change Management

- Coaching

- Consulting

- Employee Engagement

- Flow and Engagement

- Leadership

- Marketing

- Neuroscience

- Organisational Design

- Performance Management

- Personal Development Analysis (PDA)

- Personality

- Strategy

- Structural and Talent Analytics

- Systems

- Talent Management

- Training